The bison, our national mammal, is given a special day of recognition every year—the first Saturday in November is National Bison Day. Below are ten events from bison history. I’m trying to avoid the common facts you’ll find all over the Internet on Bison Day, such as—the bison is North America’s largest land animal; it once numbered 60 million animals roaming in vast herds; or 10 million; or 30 million—no one really knows, though we do know it was nearly wiped out in the wild in the 1880s and later reduced by poaching to about two dozen individuals in Yellowstone National Park, the last of the wild, free-roaming American buffalo. So, National Bison Day—here we go:

1. Theodore Roosevelt, Spare That Bison

Bison had a powerful effect upon Theodore Roosevelt, the 26th U.S. president. In September 1883, when he was not quite 25, he traveled by train to the Badlands of western Dakota Territory (now North Dakota) to hunt bison, which were nearly extinct. For weeks he rode horseback in search of the area’s last, straggling bison. The animals were skittish, since they had been hunted so hard that nearly all carried bullets in their bodies. He finally killed a bull, the head of which can be seen today at his home in Oyster Bay, New York, now a National Historic Site. As a result of this hunt, Roosevelt established two cattle ranches in the Badlands. His western experience led him to recognize that uncontrolled settlement was destroying wildlife and wild lands. In 1887 he allied with other eastern big-game hunters to launch the Boone and Crockett Club, which helped lead him to play a major role in saving the nearly extinct plains bison he had hunted relentlessly (see item 2).

2. Putting Bison Back Where They Belong

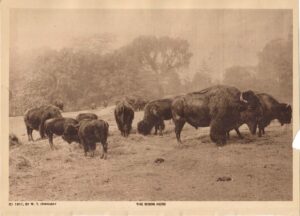

The bison figured prominently in the first U.S. effort to restore a species to an area where it had been extirpated. In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt helped pick Oklahoma’s Wichita Mountains for this ambitious experiment. In October of that year, Roosevelt and his conservationist allies, including William T. Hornaday (see item 5), the director of the New York Zoological Society (aka the Bronx Zoo), shipped 15 zoo bison to Oklahoma by train. They were released on what is today the Wichita Mountains National Wildlife Refuge, where their descendants still roam, the offspring of a successful wildlife-restoration experiment that served as a model for other reintroductions.

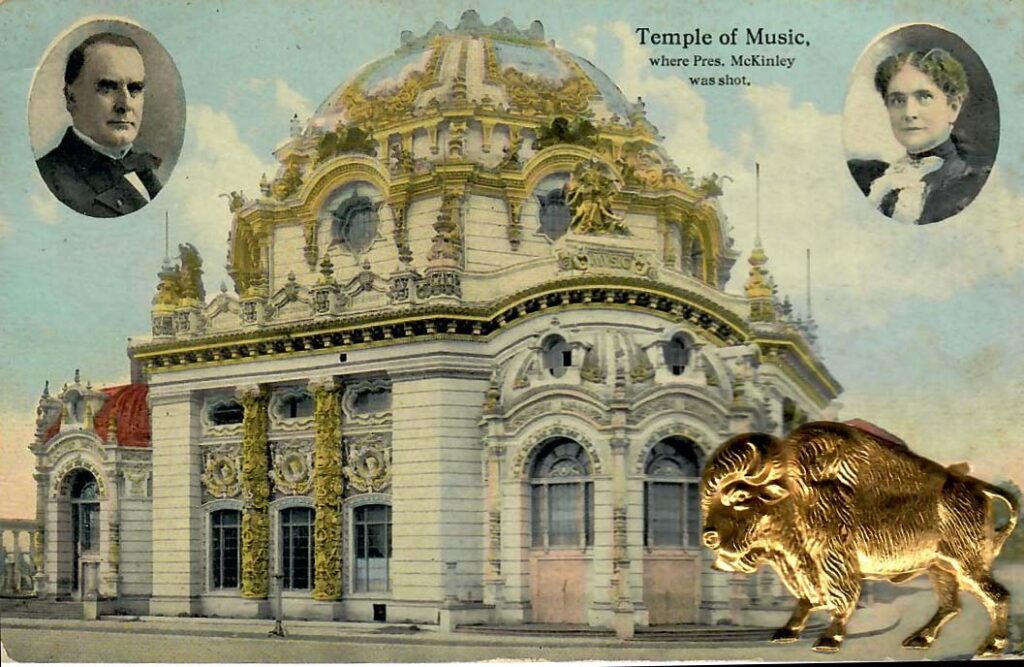

3. Bison Souvenirs

In 1901, the Pan-American Exposition, a sort of world’s fair for the Western Hemisphere, was held in Buffalo, New York. The event, which ran from May 1 to November 2, resulted in the sale of thousands of bison souvenirs, including little bronze statues, photographs of bison, artwork—myriad things that you can still find in antique shops to this day. The exposition was also the scene of a tragedy: When President William McKinley visited the exposition, he was assassinated by a mentally unbalanced radical. Theodore Roosevelt, a champion of bison restoration, ascended from the vice-presidency to the White House.

4.Home on the Range? Really?

Nearly 400,000 bison roam the United States today. They are found in all 50 states, which is not a natural thing—I mean really, bison in Hawaii? But the bison has had a strange fate. Adapted to traveling constantly across vast distances in large, migratory herds, the bison is not meant to be fenced in. But fenced it is, one way or another, either by real fences or by slaughter if straying too far from protected lands. In some states it is considered livestock rather than wildlife. Of the 400,000 in the United States today, only around 20,000 live in pastures large enough for the animals to maintain their physical and behavior health without human intervention, making them the only large, North American wildlife species that no longer roams wild. The rest of the U.S. bison are generally maintained as commercial herds raised for meat. However, the National Bison Association (http://bisoncentral.com ), which represents bison ranchers, has compiled a list of ethics regarding how ranch bison are treated, including measures to minimize handling of the animals.

5. Bison: Shoot Them Before They’re All Gone

As the bison galloped toward extinction in the 1880s, hunters like Theodore Roosevelt wanted to kill one for a trophy before they were all gone. Consider this: In 1886, the Smithsonian Institution knew that bison were almost extinct. Staff checked out the bison artifacts in the museum collection and concluded they needed new mounted specimens so the public could still see what bison looked like once the species was wiped out. So the Smithsonian response to the near extinction of the bison was to send an expedition to Montana—home to a few scattered, harried bison—and collect up to 100 specimens, including up to 30 hides, if the expedition could even find any bison. The leader of the expedition: William T. Hornaday (see item 2), who would team up with Roosevelt 20 years later to save the last, lingering bison and restore herds to the wild. Hornaday and his team killed more than 20 bison, more or less all that they saw.

6. Bison and War

Killing off the bison in the 1870s in the United States was a tactic of war, used to subdue the Great Plains Indians, who were dependent on bison for food and for products used to make tools and even shelter. When the Texas state legislature in 1875 prepared to enact a law protecting bison, General Phillip Sheridan told a joint assembly of the House and Senate that rather than being blocked from killing bison, market hunters should be supported. “They are destroying the Indians’ commissary, and it is a well-known fact that an army losing its base of supplies is placed at a great disadvantage. Send [the hunters] powder and lead, [and] if you will, for the sake of lasting peace, let them kill, skin and sell until the buffaloes are exterminated.” In Europe, the two world wars of the twentieth century allowed soldiers and poachers to nearly wipe out the last of the wild European bison, or wisent. Conservation efforts are helping to recover the species, which numbers more than 6,000 animals today. The marriage of warfare with wildlife slaughter continues. Poaching by terrorist groups in Africa, to finance their activities, is threatening the survival of species ranging from elephants and giraffes to gorillas and chimpanzees. Example: The forest elephant lost about 90 percent of its population, limited to rainforests, during the past 15 years, slaughtered for ivory.

7. Bison Bath Tubs

When bison roamed widely, they would paw depressions into the prairie, engendering small pools of water that supported various water-dependent species after spring and summer rains. In these wallows bison cooled and coated themselves with mud or dust, perhaps to keep off insects. The hunters who were slaughtering the herds in the last half of the nineteenth century would use the wallows for drinking water, when nothing else was available, and for bathing.

8. Picassos of the Pleistocene

Humans began leaving paintings in the depths of European caves starting at least 30,000 years ago. Among the most common animals found among cave paintings is the European bison or wisent, sometimes painted life size. The wisent probably ranked high in painter interests, because the animals were common meat sources. The human pathway from Europe and Asia into the New World was, you could say, paved with the bones of European bison used for food. American bison, a close relative of the wisent, continued to be a source of food and other goods for North American peoples long after the wisent was nearly extinct.

9. Do We Learn Anything from Bison?

Having almost wiped out the bison, you might think that we—having learned about the biological costs of wildlife destruction—would avoid destroying other species. Sadly, that’s not the case. Consider this: According to figures from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, in the 1990s a Russian species of smallish antelope, the saiga, numbered more than a million in an area of steppes and grasslands in Kazakhstan, Mongolia, the Russian Federation, and Uzbekistan. But by 2005 they had been reduced by poachers, who sold saiga horns for practitioners of traditional Chinese medicine, to fewer than 30,000. Tighter restrictions on poaching in Russia and other nations that harbor saiga have helped the species recover, with the population rising to perhaps 125,000 today, though numbers can fluctuate wildly. Have we learned from the bison? Not yet, but maybe. For more info, visit https://www.fws.gov/international/animals/saiga-antelope.html

10. The Meat of the Matter

The bison-ranching industry slaughters about 70,000 bison a year—about half the number of cattle that the livestock industry slaughters every day. Bison ranchers are hoping to increase the market for bison meat, noting that it has less fat than salmon and more of the omega-3 nutrients that are essential for cardiac health. Moreover, bison are less harmful to natural habitat than are cattle. They do less damage to flowering prairie plants and to water sources than do cattle, which tend to gather around water and often ruin steams and ponds. Broil or grill a bison steak—I would recommend flat iron steaks—and you will find little or no fat in the pan. You can find bison at many chain grocery stories, or google for a bison ranch in your area. Some 6,500 bison ranchers are registered with the National Bison Association (http://bisoncentral.com).

Want more information on bison? See my book on bison restoration—tentatively titled The Return of the Bison: How Restoring the American Buffalo Will Help Vanishing Species Everywhere, due in bookstores in autumn 2023. Want information sooner than that? Visit http://www.alallaboutbison.com, which truly is, exhaustively and completely, about bison (I have no affiliation with that website).