Ken Burns Documentary, "The American Buffalo"

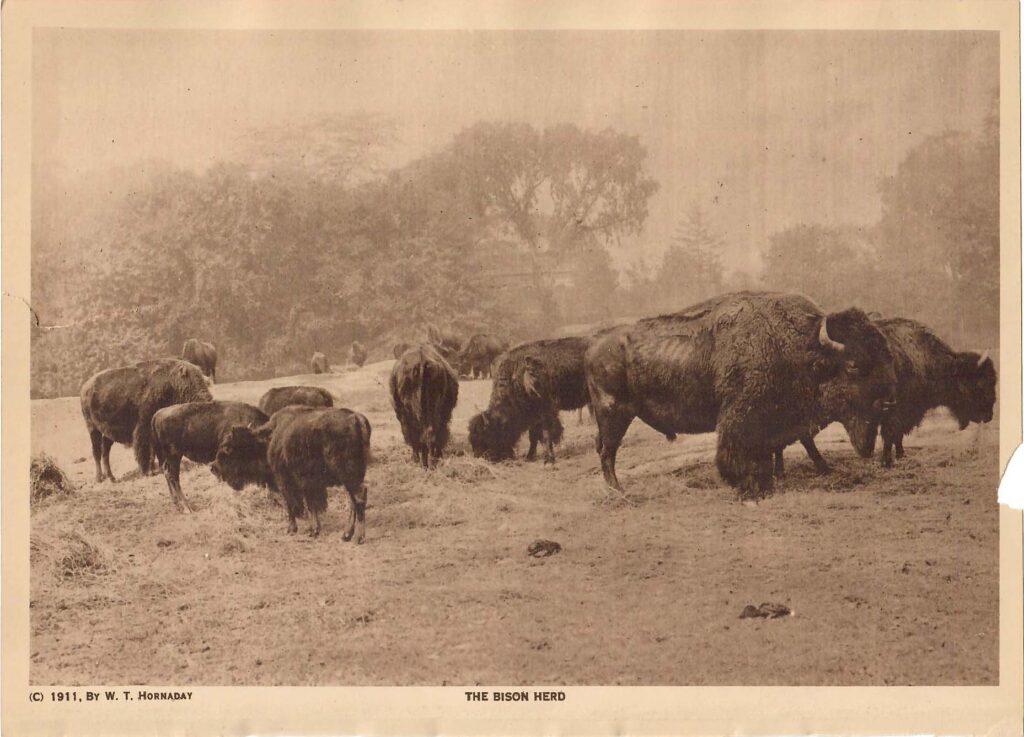

As anyone might have expected, this four-hour, two-part documentary on the destruction of the American bison and on early attempts to preserve the almost vanished species is a gem to admire. If you don’t know much about the abysmal fate of the plains bison, Episode One of this documentary will tell you all you need to know, hitting the high points and covering them well. And of course the photography is beautiful. How wonderful to see herds of bison stampeding across seemingly endless prairie. I wish the four hours had included even more bison footage. Instead, it exhibited myriad historical shots that amply reinforced the narrative of the film. Some of the photos you will see in almost any book on bison, and others were something that I, at least, have not seen despite my many years of reading about bison. The photos of Ernest Baynes, one of the early proponents of bison protection, were revelatory.

Episode Two covered the earliest days of bison conservation, when ardent conservationists fought the prevailing American attitude that wildlife was there to be marketed or summarily wiped out for the benefit of land development. These two hours focus roughly on the 1870s to 1920 and give short attention to bison recovery more or less after the mid-1930s. The film does offer passing comments on bison today but no discussion about the many problems that imperil the species. Just a comment or two or three from talking heads, who are largely writers and historians. I don’t recall comments from a single biologist, which I think would have added a missing dimension of credibility and nuance to the film. Maybe Burns feels that aspect is already covered on nature shows. Moreover, the “America” in the title The American Buffalo means United States of America, as the film scarcely nods at the presence and history of Canadian and Mexican bison and does not mention the wood bison, a slightly larger version native to northwestern Canada and Alaska; and, since the film is about U.S. bison, there is no flicker of recognition of the European bison, commonly called by the German name, wisent, which came even closer to extinction than its North American relative.

Nevertheless, the film, even if you are a bison aficionado familiar with bison history, is a pleasure to watch and then perhaps to watch again. I won’t comment on the companion book, as my book, The Return of the Bison: A Story of Survival, Restoration, and a Wilder World, was published September 1 by Mountaineers Press, so I might have a conflict of interest.